Introduction: Welcome to 1980s Technology That Still Works Better Than Your Cell Phone

Look, here’s the thing about APRS messaging that nobody wants to tell you: it’s basically text messaging for people who understand that centralized communication infrastructure is one good solar flare away from being absolutely useless. You know what I love about ham radio? When the cell towers go down—and they will go down—we’ll still be sending packets through the ionosphere like it’s nobody’s business.

This document is your comprehensive guide to the four primary methodologies for transmitting and receiving APRS (Automatic Packet Reporting System) messages. We’re talking about digital packet radio here, folks—not your fancy iPhone with its proprietary messaging protocols and planned obsolescence. This is the real deal: RF-based data transmission using the AX.25 protocol at a blistering 1200 baud. Yeah, you heard that right—1200 baud. That’s slower than a dial-up modem from 1995, but it works when literally nothing else does.

Now, before we dive into the technical minutiae, let me be crystal clear about something: this guide assumes you already know how to configure APRS on your radio. If you’re looking for button-pushing instructions for your Kenwood TM-D710 or Yaesu FTM-400, go read the manual. I know, reading manuals is like eating your vegetables—nobody wants to do it, but it’s good for you. This document focuses exclusively on the message formatting protocols and delivery mechanisms. The nitty-gritty. The good stuff.

A Quick Word About Variables

Throughout this guide, you’ll see text enclosed in angle brackets like <Call Sign> or <Message>. These are variables—placeholders that you replace with your actual data. If you try to literally send a message to someone called <Call Sign>, well, congratulations, you’ve just discovered why we can’t have nice things.

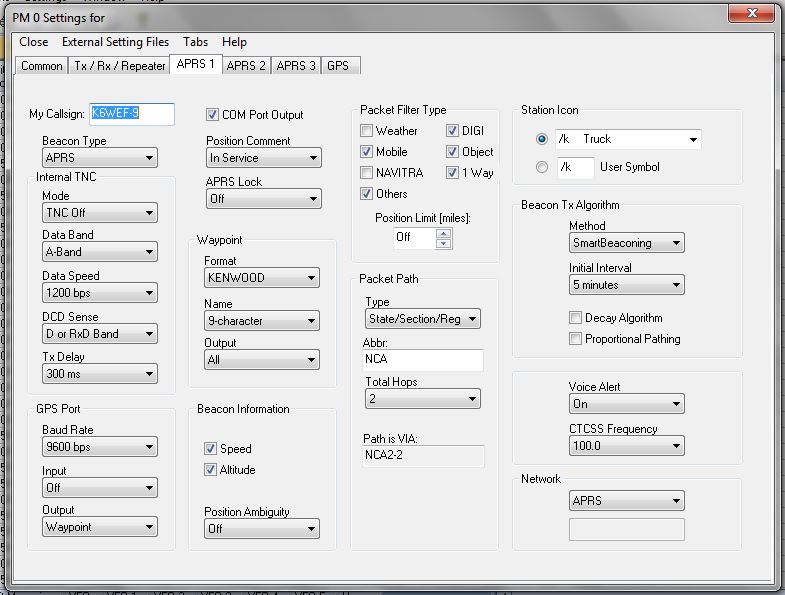

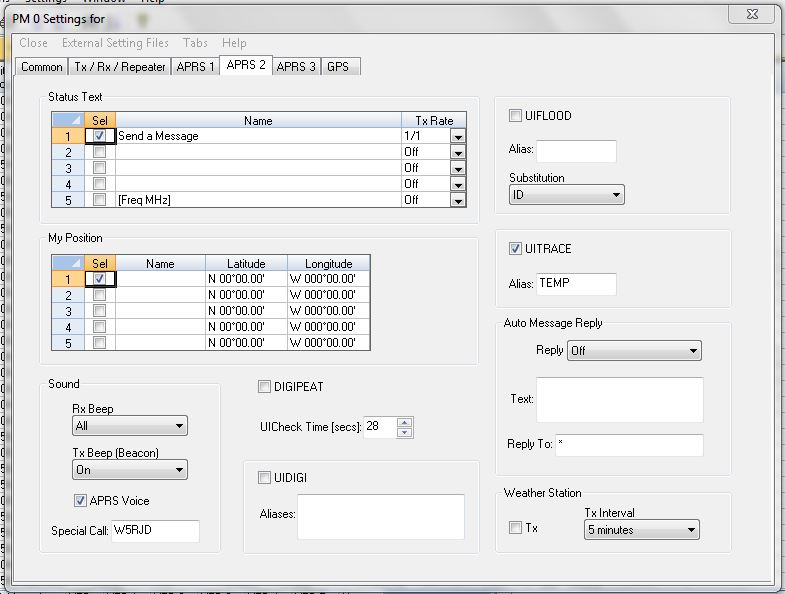

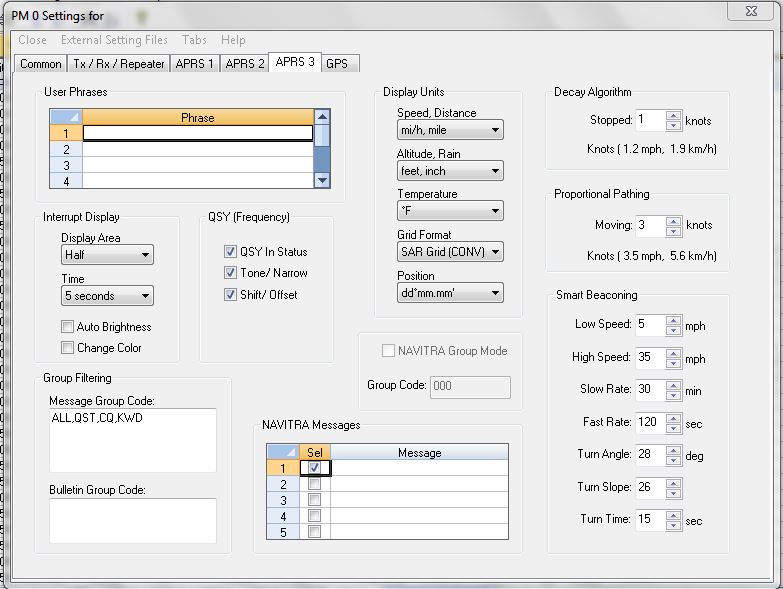

Image Credits: All supporting visual materials in this document were graciously provided by Butch, K6WEF, who clearly has better graphic design skills than most of us have Morse code proficiency. Thanks, Butch.

Section 1: Direct Radio-to-Radio APRS Messaging (The “Hope They’re Actually Listening” Method)

1.1 The Technical Overview

This is the most straightforward APRS messaging format, and by “straightforward,” I mean it’s as reliable as your buddy actually showing up on time to help you move. This method transmits APRS messages directly from your radio to another operator’s radio via RF (Radio Frequency) propagation. The message travels through the amateur radio spectrum—specifically the APRS frequency (144.390 MHz in North America, because apparently every other region needed to be different just to keep things interesting).

Here’s the catch, and it’s a big one: the recipient must be on the air, running APRS, and within radio range of a digipeater network at the exact moment you send the message. If they’re not? That message disappears into the electromagnetic void like it never existed. No store-and-forward. No delivery confirmation. No nothing. It’s like shouting into the wind and hoping someone hears you.

1.2 The Format Specification

The protocol format is deceptively simple:

TO: <Call Sign>-<SSID>

MSG: <Message Text>

Let me break this down for those of you who haven’t memorized the APRS specification:

The TO Field:

- Call Sign: This is the FCC-issued amateur radio call sign of your intended recipient. You know, that thing that cost you $35 and requires you to remember random alphanumeric combinations for the rest of your licensed life.

- SSID: The Secondary Station Identifier, which is a suffix number ranging from 0-15. This brilliant piece of protocol design allows one call sign to operate multiple APRS stations simultaneously. Common conventions include:

-7for handheld transceivers-9for mobile installations-5for generic stations- But honestly, people use whatever the hell they want, so good luck guessing.

The MSG Field: This is your actual message content, limited to 67 characters because back when Bob Bruninga designed APRS in the 1980s, memory was expensive and nobody anticipated we’d need to send entire dissertations via packet radio. Keep it concise, folks.

1.3 Practical Example

Let’s say you’ve just arrived at a remote camping location and want to notify your buddy Paul (KD8BXY) that you made it safely:

TO: KD8BXY-9

MSG: Hello Paul, arrived safely, no cell service.

This message will propagate through the APRS digipeater network (assuming you’re within range of one) and eventually reach Paul’s mobile APRS station (SSID -9). If Paul is monitoring. If his radio is on. If the digipeaters are working. If there’s no RF interference. You see where I’m going with this?

1.4 The Limitations You Need to Know

Here’s what they don’t tell you in the quick-start guide:

- No Store-and-Forward: If the recipient isn’t actively monitoring, your message evaporates faster than your New Year’s resolutions.

- No Delivery Confirmation: Unless the recipient manually acknowledges your message, you have no idea if it was received.

- Range Dependency: You’re at the mercy of digipeater coverage, which in some parts of the country is excellent, and in others is “Why the hell did I move here?”

- Channel Congestion: APRS operates on a single shared frequency. High-traffic areas can experience packet collisions, resulting in message loss.

Section 2: Server-Based APRS Messaging (The “Actually Reliable” Method)

2.1 The Fundamental Architecture

Now we’re talking about a system that actually makes sense for anyone who occasionally needs to, you know, receive messages. This methodology leverages APRS-IS (APRS Internet Service), a global network of servers that provide store-and-forward message capability. Think of it as voicemail for packet radio, except it actually works.

When you send a message using this format, it doesn’t disappear into the ether. Instead, it’s stored on an APRS message server—an actual physical server somewhere on the Internet that runs 24/7/365, unlike that one guy in your ham club who promises to monitor the local repeater but never does.

The architectural beauty here is the decoupling of sender and receiver presence. You don’t need simultaneous RF connectivity. You don’t need the recipient to be on the air. You just need the APRS-IS infrastructure, which has proven to be remarkably reliable considering it’s maintained primarily by volunteers who probably have actual jobs.

2.2 Sending Messages via the MAIL Gateway

Format Specification:

TO: MAIL

MSG: @<Call Sign>-<SSID> <Message Text>

Notice the critical @ symbol prefix before the recipient’s call sign. This is not optional. This is not a suggestion. This character tells the APRS message server “Hey, this is for someone specific, not just random chatter.” Without it, your message goes nowhere, and you’ll spend the next hour troubleshooting before you realize you forgot one ASCII character.

Technical Deep Dive:

When you transmit this message format:

- Your APRS-enabled radio encapsulates the message in an AX.25 UI frame

- The frame is transmitted via FM modulation on the APRS frequency

- Local digipeaters relay the frame across the terrestrial RF network

- An Internet Gateway (IGate) receives the frame and forwards it to APRS-IS via TCP/IP

- The APRS-IS server parses the destination field (MAIL) and routes accordingly

- The message server stores the message in a queue associated with the recipient’s call sign

- The message remains queued until retrieved or expires (typically after 30 days, because server storage isn’t infinite)

Practical Example:

Let’s say your buddy’s Echo Link node has gone offline, and you need to alert him:

TO: MAIL

MSG: @KA8OAD-7 Echo Link node is Off-line.

This message will be stored on the APRS message server and delivered when KA8OAD-7 requests message retrieval. It’s like leaving a note on someone’s door, except the door is on the Internet, and the note is in packet radio format.

2.3 Retrieving Server-Stored Messages

Here’s where it gets interesting. To retrieve your waiting messages, you transmit a specific command sequence to the MAIL gateway:

Format Specification:

TO: MAIL

MSG: APRSM

That’s it. Four letters: APRSM. This is your “check messages” command. When the server receives this request from your call sign, it retrieves all queued messages and transmits them back to you via RF.

The Technical Process:

- Your radio transmits the APRSM request

- The request propagates to an IGate and reaches APRS-IS

- The message server queries its database for messages addressed to your call sign/SSID

- All pending messages are formatted into APRS message frames

- The server transmits these frames back through APRS-IS

- An IGate converts the messages back to RF

- Your radio receives and displays each message sequentially

Important Considerations:

- Messages are delivered in FIFO (First In, First Out) order

- Multiple messages may take time to transmit due to APRS channel timing

- Message delivery acknowledgment is automatic but not instantaneous

- You can check messages as frequently as you want, but don’t be that guy who spams the network every 30 seconds

Section 3: APRS-to-SMS Gateway Integration (Because Sometimes You Need to Reach the Civilians)

3.1 The Cross-Platform Communication Challenge

Let’s face reality: most people don’t have ham licenses, don’t own APRS-capable radios, and think “digipeater” is some kind of Internet buzzword. But sometimes you need to communicate with these people anyway. That’s where the APRS-to-SMS gateway comes in—a bridge between our glorious packet radio ecosystem and the mundane world of cellular telecommunications.

The SMS gateway service accepts APRS messages and converts them into standard SMS text messages deliverable to any cellular phone in North America. It’s like having a translator who speaks both packet radio and cell phone tower.

3.2 Sending Messages from Radio to Cell Phone

Format Specification:

TO: SMS

MSG: @<10-digit Cell Number> <Message Text>

Technical Implementation Details:

The destination field SMS routes your message to the APRS-SMS gateway service. The message content begins with @ followed by a 10-digit North American phone number (country code +1 is assumed). The gateway strips the APRS protocol overhead, reformats the message into SMS format, and delivers it through cellular networks via commercial SMS aggregation services.

Character Limitations:

SMS messages are technically limited to 160 characters using GSM-7 encoding, but the APRS message overhead, call sign inclusion, and protocol formatting reduce your usable character count to approximately 140 characters. Plan accordingly. This is not the medium for sending your manifesto.

Practical Example:

Suppose you’re stranded and need assistance:

TO: SMS

MSG: @1234567890 Need assistance.

The recipient receives a text message that appears to come from the APRS gateway service, with your call sign included in the message body. They can reply using the reverse protocol (detailed next).

3.3 Sending Messages from Cell Phone to Radio

Format Specification:

From the cell phone, send an SMS to:

TO: 866-352-4096

MSG: @<Call Sign>-<SSID> <Message Text>

This is the APRS SMS Gateway’s dedicated phone number—essentially a two-way bridge between cellular and APRS networks. The gateway receives the SMS, extracts the destination call sign from the message content, and reformats it as a proper APRS message for RF transmission.

The Reverse Path Technical Flow:

- User sends SMS to 866-352-4096 from their cellular device

- Message routes through cellular carrier infrastructure

- SMS gateway receives and parses the message

- Gateway extracts recipient call sign and message content

- Message is encapsulated in APRS format

- APRS-IS receives and queues the message

- IGate transmits message via RF on APRS frequency

- Recipient’s radio receives and displays the message

Practical Examples:

Cell Phone Transmission:

TO: 866-352-4096

MSG: @WB8YYS-7 When does the Net start tonight?

How It Appears on the Recipient’s Radio:

FROM: SMS

MSG: @9876543210 When does the Net start tonight?

Notice that the sender’s phone number replaces their call sign (because they don’t have one—they’re civilians, remember?). The APRS radio displays the message with SMS as the source identifier and includes the sender’s phone number for reference.

Critical Limitations:

- Message delivery is dependent on both cellular and APRS network availability

- There may be delays ranging from seconds to minutes

- Some cellular carriers may block short code SMS services

- International numbers are not supported without special gateway arrangements

- Your cellular carrier may charge standard SMS rates (though most plans include unlimited texting these days, assuming your carrier isn’t trying to screw you)

Section 4: APRS-to-Email Gateway (For When You Need a Paper Trail)

4.1 Email Integration Architecture

Email integration represents the ultimate in asynchronous communication. You’re transmitting from a radio to someone’s email inbox—bridging analog RF transmission, digital packet protocol, Internet infrastructure, and store-and-forward email servers. It’s a technological miracle that this works at all, frankly.

The APRS email gateway accepts specially formatted messages and converts them into proper RFC 5322-compliant email messages. These are delivered through standard SMTP (Simple Mail Transfer Protocol) to the recipient’s email server, where they sit in an inbox like any other email, complete with subject lines, headers, and all that jazz.

4.2 Format Specification

Radio Transmission Format:

TO: EMAIL

MSG: <email-address> <Message Text>

Note the absence of the @ prefix before the email address—this is different from the SMS and MAIL formats, because apparently consistency is too much to ask for in amateur radio protocols. The email address must be a fully qualified address including the domain (e.g., username@domain.com).

Technical Processing Flow:

- Your radio transmits the APRS message with EMAIL as destination

- Message propagates through digipeaters to an IGate

- IGate forwards to APRS-IS via Internet connection

- Email gateway receives and parses the message

- Gateway constructs an RFC 5322 email message with:

- FROM field: Your call sign +

@aprs.earth(or similar gateway domain) - TO field: Recipient’s email address

- SUBJECT: Typically “APRS Message from [Your Call Sign]”

- BODY: Your message content

- FROM field: Your call sign +

- Gateway submits email to SMTP server

- SMTP infrastructure delivers to recipient’s email server

- Message appears in recipient’s inbox

4.3 Practical Implementation

Radio Transmission Example:

TO: EMAIL

MSG: KD8BXY@Hotmail.com I will be in route to home soon!

Resulting Email:

TO: KD8BXY@hotmail.com

FROM: <Your Call Sign>-<SSID>@aprs.earth

SUBJECT: APRS Message from <Your Call Sign>

BODY: I will be in route to home soon!

4.4 Critical Limitations and Considerations

The Spam Problem:

Here’s the dirty little secret: APRS-to-email messages frequently end up in spam folders. Why? Because email servers see messages originating from unusual domains (like aprs.earth) sent through third-party gateways and think “This smells like spam.” Modern spam filters use sophisticated heuristics, and APRS email messages often trigger multiple red flags:

- Non-standard originating domain

- Lack of proper SPF/DKIM/DMARC authentication

- Generic gateway headers

- Unusual routing paths

Solution: Add the APRS email gateway address to your email client’s contact list or whitelist. This trains the spam filter to recognize these messages as legitimate.

The One-Way Street:

Email recipients cannot reply to these messages. The return address (something@aprs.earth) is a non-monitored address. If they hit “Reply,” their message goes into a digital black hole. If you need two-way communication, use a different method or provide alternative contact information in your message content.

Message Formatting:

- Keep messages concise—you have limited characters

- Don’t include excessive punctuation that might trigger spam filters

- Avoid ALL CAPS (unless you’re actually yelling)

- Include context since the recipient won’t have APRS background

Section 5: Automatic Message Waiting Notification (Because Checking Manually is for Chumps)

5.1 The APMAIL Beacon Service

The APRS message server includes an optional notification service that alerts you when messages are waiting for retrieval. Instead of periodically transmitting APRSM queries like some kind of obsessive-compulsive packet radio operator, you can enable automatic notifications that inform you when new messages arrive.

This is implemented through a simple beacon text inclusion. When the message server detects messages queued for your call sign and sees that you’re beaconing the magic keyword, it automatically sends you a notification message.

5.2 Implementation

Enable Notifications by Including in Your Position Beacon:

APMAIL

That’s it. Just include the text string APMAIL somewhere in your APRS position beacon comment field. The message server monitors position beacons for this keyword and maintains a list of stations requesting notification.

Technical Operation:

- Your APRS radio transmits periodic position beacons (as APRS devices do)

- Your beacon comment text includes

APMAIL - The message server observes your beacon via APRS-IS

- Server adds your call sign to the notification subscriber list

- When new messages arrive for you, the server automatically transmits:

FROM: MAIL MSG: You have messages waiting. - Your radio receives this notification and alerts you

- You transmit the retrieval command (APRSM) to collect your messages

Benefits:

- No need to manually check for messages repeatedly

- Reduces unnecessary APRS traffic from constant polling

- Real-time awareness of incoming communications

- Lower battery consumption on mobile/portable stations

Considerations:

- Notification delivery depends on RF propagation and IGate availability

- Multiple messages may arrive between notifications

- You still need to manually request message retrieval after notification

- Disabling is as simple as removing

APMAILfrom your beacon

The Beautiful Complexity of Amateur Radio Digital Communications

Look, APRS messaging isn’t perfect. It’s not as instant as WhatsApp. It’s not as feature-rich as Signal. It’s definitely not as sexy as that new encrypted messaging app the kids are using. But here’s what it is: it’s resilient, it’s distributed, it’s independent of commercial infrastructure, and when everything else fails—and everything will fail eventually—APRS will still be chugging along at 1200 baud, sending your packets through the ether like it’s 1985.

The protocols outlined in this document represent decades of amateur radio innovation, community collaboration, and practical engineering. They’re not always elegant. They’re not always intuitive. But they work, and that’s what matters when you’re sitting on a mountain without cell service, or when the Internet goes down, or when you just want to communicate without Mark Zuckerberg data-mining your conversations.

So get out there, set up your APRS station, and start sending some packets. And when someone asks you why you’re still using “outdated” technology from the 1980s, you can smile and say, “Because I like technology that actually works.”

73 W6SAL

Additional Resources

- APRS Specification: Review the complete APRS protocol specification at how.aprs.works

- APRS-IS Servers: Check current server status and network health at APRS Tier 2 Network

- Visual Guides: Special thanks again to Butch, K6WEF, for providing the visual documentation that makes this guide possible

Remember: When everyone else is staring at their dead smartphones wondering why the cell towers aren’t working, you’ll be the one sending packets like it’s nobody’s business. That’s the amateur radio difference.

6. Butch’s Kenwood D710 APRS Settings